Carved Reflections

Filtered Exhibition | Ottawa Art Gallery | July 26, 2021 to December 24, 2021

Sarah-Mecca Abdourahman and Laurena Finéus

These two artists like many diasporic Canadians, grew up contending with media coverage of their families’ country of origin, filtered through technologies and screens. While Finéus digested a constant flow of harmful images and narratives of Haiti’s devastation by its 2010 earthquakes, Abdourahman similarly felt inundated by references to the poverty and violence of both Somalia in India. As young Black Canadians, these two artists had a common feelings of unease, numbness, and disconnect in relation to this, and they asked, “what are the impacts of growing up immersed in this westernized digital culture?”

The artists described their co-creation of this installation as “creating a submerged experience of the diasporic consciousness, and presenting the viewer with the various stages of Black existence.” The audio heard in the room is a combined cascade of sound clips from news media and oral storytelling, a tradition common both Haiti and Somalia. This at once references that continuous street noises that accompanies the viewing of urban art, and doubly serves to recreate the overstimulating environment of having to filter this media.

As a critique of the filters that inform the lived experiences of many Black Canadians, the work proclaims visual agency over these narratives through their re-presentation.

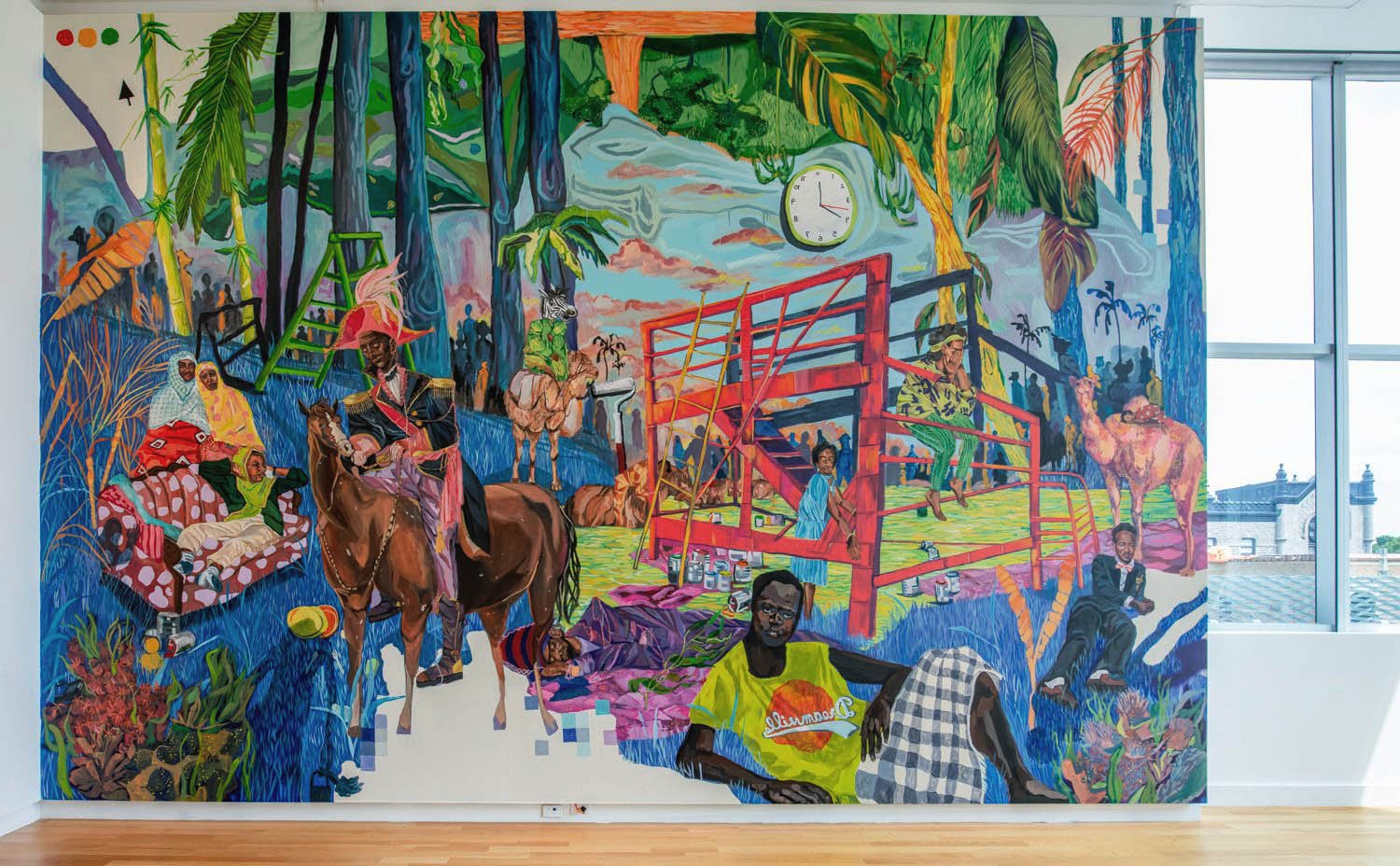

Biyaha hoostooda / Under the water, 2021

Acrylic latex paint

666.8 cm x 457.2 cm

Have you ever been haunted? It is a feeling of unease, fatigue, and drowsiness always weighing on your shoulders.

There is a lethargy that derives from having to filter deaths continuously. The effects of living a filtered reality are similar to being stuck in a dream where you never know what’s authentic or deceptive. It is a nightmare and a paralyzed reality of who we are. This is especially true as a young diaspora, in this search for news and media that truly represents what is happening in your country of origin.

By using the Somali word “Biyaha hoostooda” to convey a Haitian understanding of an underwater resting place, the title illustrates the pan African connection between our practices. The Somali term “Biyaha hoostooda” is a translation of the kréyol concept of “anba dlo,” meaning that one has sunk beneath the waters. In Haitian mythology, “anba dlo” is considered to be the watery grave where ancestral spirits went to rest during the crossing of the Middle Passage. “Anba dlo” is also linked to the kréyol term “Lot bo dlo,” referring to the diasporic experience of being established somewhere other than the mainland.

This mural is the first work encountered by visitors as they enter the space. It is a world where we wanted to showcase “rest as power.” What does it look like to see Black bodies simply resting in a larger-than-life landscape? They are not fighting, agonized, or dead.

We have chosen to depict important historical figures from both of our cultures. Jean-Jacques Dessalines was a general that led Haitians to freedom and the very first ruler of the country in 1805. Mahamoud Harbi Farah, the Vice President of French Somaliland (now Djibouti) initiated the pan-Somali movement in the 1950s. These impactful leaders fought for the freedom of our ancestors, and subsequently ours.

But we forget that these idealized heroes were also humans and needed to rest. As we keep fighting the same fight they did, we link our subconscious to theirs by illustrating members of our own families sleeping nearby. The souls of those we have lost, and continue to lose in these battles, are illustrated as shadows throughout the piece.

This underworld in which the bodies are resting showcases an inner battle that comes from confronting painful images of our people, evoking a rise of emotions of compassion, fatigue, and numbness.

Construction material like metal scaffolding are included in the composition, creating an industrial-looking landscape to enforce the idea of “man-made” and the weight attached to this fatigue. Certain surreal elements are also included to allude to the absurdity fundamental to dreams. Just like this underworld, historically the sufferings of our ancestors' bodies were often “man-made”: created by the perpetrator. This industrial landscape is symbolic of the unfair dynamic towards our people. The resting bodies are stuck in this nightmare. It is not a casual rest, but rather a necessary rest.

Lòt bò dlo / On the other side of the water, 2021

Mixed media (Acrylic latex paint, wheatpaste and spray cans)

792.5 x 457.2 cm

This mural showcases the pure and joyful communion of a family on a beach, offering a visual counter-narrative that serves to humanize migrant families. There's been a disproportionate digital consumption of Black pain and grief throughout 2020 and 2021. This mural brings back an important sense of normalcy to our community, and offers the viewer an instant sense of warmth.

The use of wheatpasting in this mural bridges our studio practice with the nature of street art. This speaks to the activist/political history of wheatpasting, and how it has given a voice to marginalized communities for decades.

We went through each other’s archives and talked about our memories of family, feasting, and happiness. We explored our distinct ideas around healing. We wanted to create a work that would speak directly to our Black audiences and invite them to feel at peace.

The water as a gateway to healing seemed particularly intrinsic to both of our diasporic identities. Abdourahman’s family had a playful relationship with water, describing it as a window towards escape. By contrast, as a descendant of slaves from the transatlantic trade, Finéus was taught to fear the water and the many souls it still holds of her ancestors. Our title Lòt bò dlo, is a Kreyòl phrase that stands for both promise and peril, hope and despair, when speaking to the journey of Haitian migrants coming to North America. They often died at sea, and for those who did make it to the foreign land, they were welcomed by waves of xenophobia that continues today. Those who make up the current population are memorialized in the media as dead bodies invading precious touristic shores.

Serving as a radical action to reclaim space and showcasing a reality centering Black joy instead of touristic pleasures/fun, we physically carved out inhabiting tourists from the pristine shores of touristic beaches.

The organic nature of what looks to be a gigantic collage is aiming at giving our viewer an intimate and private look into this moment of pure freedom. It is through our time spent with our loved ones that we can heal and demonstrate joy that is separate from the filter of violent images and media references provided in the digital space.

Have you ever been haunted?, 2021

Acrylic latex paint and spray cans

516.3 x 457.2 cm

Every child of colour goes through an obsessive phase online, which is supported by the evident lack of media representation. These children want to understand why they are different and cannot look like the majority. This initiates an elaborate deconstruction of identity beginning from an early age. Of course, concepts of race and concepts of racial identity are difficult for children to understand and identify. For children of immigrants, discussions, and understanding of race are either brief or avoided. In reality, race can only be explained through lived experiences. Children can sense and compare experiences of being racialized, and are aware that they are unlike others.

These childhood portraits aim to illustrate this concept of being “othered.” The mural is a way to reflect the disassociation that begins to occur in minds of Black children when they become increasingly aware of the disturbing images of their communities online and in the media. These portraits also served as an exercise for the artists, to get back in touch with their younger selves, providing themselves with a sense of empathy that was never received.

American author Zora Neale Hurston’s description that “I feel most coloured when I am thrown against a sharp white background” is relatable to many (“How It Feels to Be Colored Me, ” 1928). In early childhood, we are mostly surrounded by our community: people that look like us. However, it is when we enter institutions like preschool or kindergarten for the first time that we realize the differences in our appearance. There are real-life consequences to being exposed to these differences, which can be posed as ideals, constantly from life and in the media. We might start to compare ourselves to these broken images of people like us: concluding that our bodies are “othered.”

These self-portraits investigate the often-linear white gaze. This early childhood awakening is when we start to experience moments of hypervisibility and invisibility as determined by white spaces. We want to examine this aspect of identity through our carved self-portraits, made out of photos from our childhood albums. In this work we had the power to construct how we perceive ourselves, showing a more vulnerable and personal aspect of us.

Photo credit: Justin Wonnacott